2022 HOMOSASSA RIVER RESTORATION PROGRESS REPORT

2022

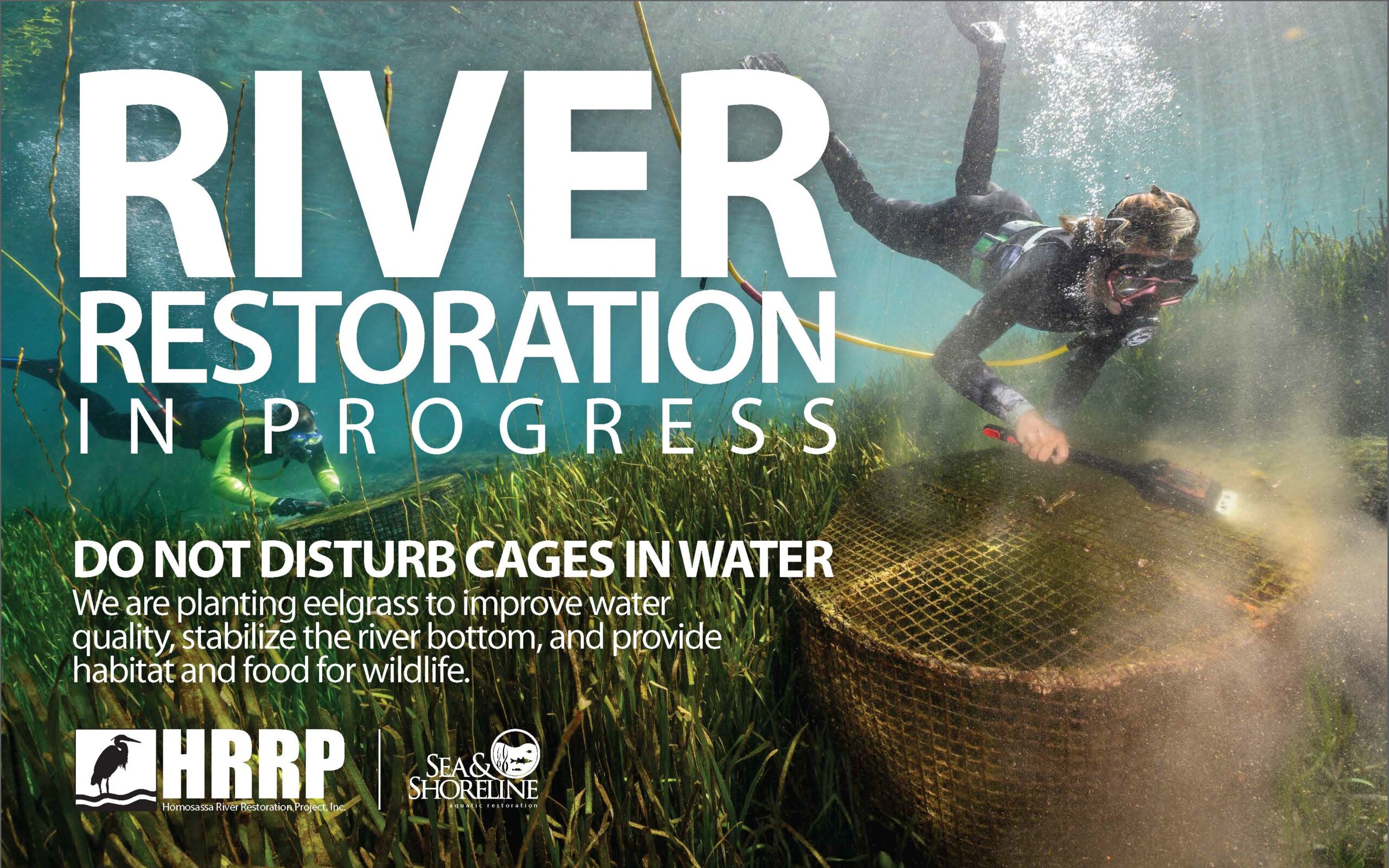

The beginning of the winter manatee season on November 15, 2022 marked the end of another successful season for the Homosassa River Restoration Project. Another step forward in our continuing efforts to rid the river of Lyngbya and years of accumulated detrital material as well as plant and restore healthy eelgrass meadows. Additional spring vents were uncovered and grasses installed in 2021 continue to flourish and expand.

Strong local community support helped pave the way for three very successful fundraisers allowing HRRP to continue permitting into Phase 4 and expand educational and community programs.

HRRP went to Tallahassee to lobby our Legislators for the funding need to continue our efforts.

FACTS AND NUMBERS

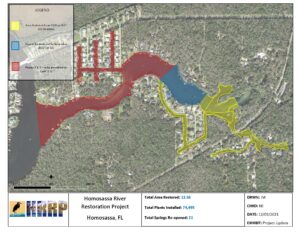

Phase 1 is now complete.

Area restored: 23.69 acres.

Muck removed: 120 Million Pounds.

Eelgrass Plants Installed: 130,445

Grow SAV Herbivory Exclusion Cages: 1004 were removed from last years use and 1,060 installed this year.

Uncovered Spring Vent Count: 22

Phase 2 and 3 DEP Permitting: Combined 26 acres of river and canals

LOOKING AHEAD TO 2023

State Funding for 2023 did not meet expectations. Beginning April 1 Sea & Shoreline crews will be back in the water working on Phase 2. How far the project moves ahead will depend on whether any additional funding is available. HRRP members will once again be walking the halls of the Capital Building this spring meeting with your state representatives.

The Homosassa River Restoration Project is a multi year, multi million dollar restoration project being completed by a small all-volunteer 501(c)(3) in partnership with state agencies. Government/Private partnerships completing projects of this magnitude are extremely rare.

Without the support and trust of our former Senator and now Florida Commissioner of Agriculture Wilton Simpson and Representative Ralph Massullo these projects never would have seen the light of day.

HRRP would like to welcome our newly elected State Senator Blaise Ingoglia and look forward to working with him.

The State Agency overseeing our project is The Florida Department of Environmental Protection and is responsible for and in overall control of the funding, contracts, and the oversite required to make sure that your taxpayer dollars are spent wisely and as intended.

WHAT YOU CAN DO

- Watch out for exclusion cages. Look before anchoring. Use sand anchors, spud and/or power poles DO NOT DRAG ANCHORS! Tilt up when in shallow waters.

- Continue to follow our progress on this website and LIKE US on Facebook.

- Happen to find yourself in front of Sen. Blaise Ingoglia and/or Rep. Ralph Massullo? Thank them for their support and ask that they continue.

- Donate to HRRP

A River in Decline

A long, slow decline

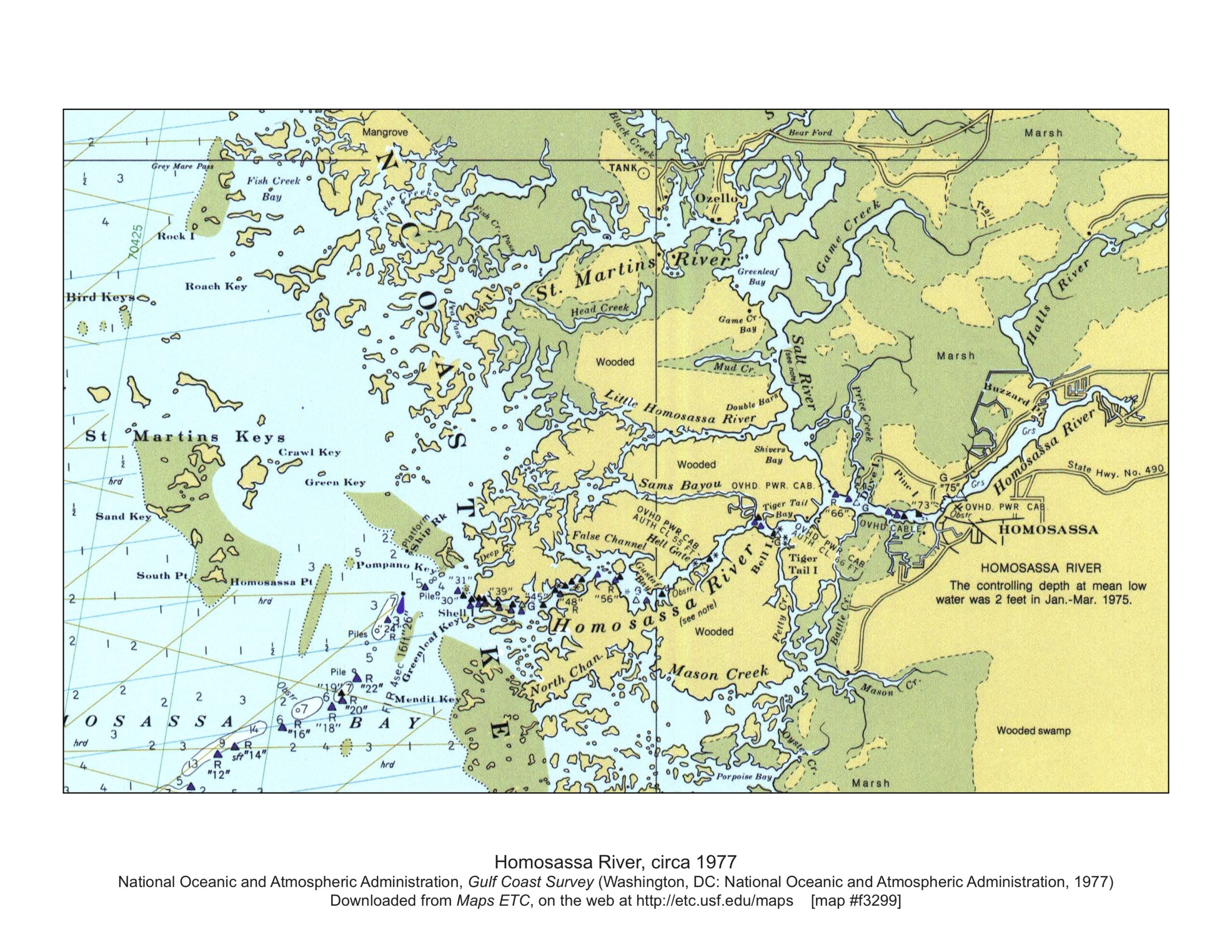

The Homosassa River has been in a steady decline for decades. Our once beautiful river has turned black with pools of green slime. Algae dominates the ecosystem. Nitrate and salinity levels are at record highs. Lyngbya Algae (the green, stringy blobs that mushroom all summer) smothers other native plant life.

Water clarity, along with oxygen levels, are decreasing. The river grasses, once lush habitat for fish and other water wildlife, have all but disappeared. Layers of muck often measured in feet now cover the natural sand and limestone river bottom. All these combine to destroy one of the most beautiful and vibrant gems of the Florida’s springs system.

Clogged up springs

Organic matter or “detritus” compacts on the bottom of the river and its tributaries. This packed muck covers the ground and prevents new growth. This mass of detritus also covers up spring vents and boils.

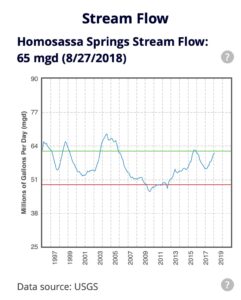

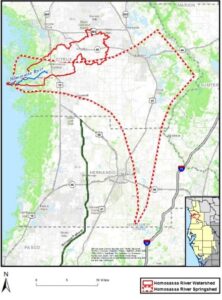

The Southwest Florida Water Management District maintains a dashboard on Homosassa Springs here.

Restoration Thinking

Restoration efforts begin at the river’s headwaters and work their way downstream. We remove the detritus that is blocking the springs and help increase the flow of the river. Water moves westward from central Florida toward the coast. If it can’t escape in the river’s headwaters it continues underground further toward the Gulf of Mexico. Clogged spring vents and boils have reduced springs output. Cleaning those vents and boils increases river flow. Learn about healthy springs here.

Species decline

As waters become more stagnant and have less oxygen, the variety of species that can survive in the river declines. Crabs and fish species leave, having too little to sustain them. As algae takes over, the clams and worms needed by crabs are choked out. Low oxygen dead zones result.

Pollution

For our waterway, fertilizer runoff and leaky septic systems are the worst polluters.

With fewer plants to absorb and remove these nutrients, the problem becomes progressively worse over time.

Pollution isn’t limited to nutrients. In addition to carelessly discarded plastic bottles, another “natural” pollution threatens the river. Scalloping is a popular summer activity, and the sea grass beds off the coast of Citrus County offer great fishing. But while those scallop shells will decompose in salt water, they will remain in fresh water for decades. People enjoying their scallop catch have taken to throwing the shells in fresh water, creating a long term problem that covers the floor of the river. Effectively creating a concrete bottom.

We can make a difference in the way that our rivers support life. Make the river a priority. Keep fertilizer use within miles of the coast to a minimum. Support efforts to share important environmental information with the public. Share our posts on social media. Talk to your friends and neighbors. We can restore this river together.

We can make a difference in the way that our rivers support life. Make the river a priority. Keep fertilizer use within miles of the coast to a minimum. Support efforts to share important environmental information with the public. Share our posts on social media. Talk to your friends and neighbors. We can restore this river together.

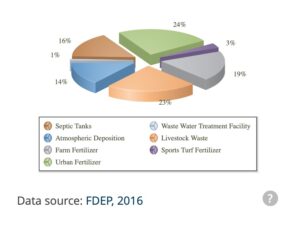

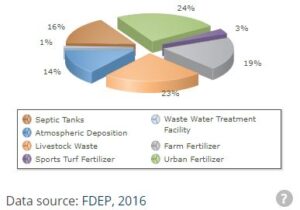

Residential Fertilizer & Groundwater Nitrates

Groundwater Nitrates and Fertilizer

Fertilizer is one of the major sources of nitrates

in Florida’s groundwater. The Florida Department of Environmental Protection BMAP for the Homosassa watershed breaks down the separate categories of nitrate loading. Over 40% of groundwater nitrates are linked to fertilizer use. Residential use contributes to over half of that total. Fertilizer nitrates are easily picked up by storm-water as it flows across yards and gardens and directly into our rivers. Any excess fertilizer not absorbed by plants can leech into the soil and into the aquifer.

Why high levels matter

High levels are directly related to severe algae blooms. Lyngbya is a filamentous algae suffocating the native grasses of the Homosassa River. High nitrates, low oxygen, low light are perfect conditions in which algae thrives. Besides being unsightly and having an unpleasant smell Lyngbya also contains toxins harmful to human skin. When algae dies it consumes oxygen in water further exacerbating the problem. By lowering the nitrate levels we eliminate one of the factors necessary for Lyngbya to survive. We remove legacy nitrates during the restoration process . Ultimately you want to limit them in the first place.

What You Can Do

Each of us can do our part to help lower the nitrates entering our aquifer. When and how you fertilize is your responsibility. You can also:

- Urge the Citrus County Commission to implement stricter fertilizer ordinances and follow ones currently in place

- Minimize fertilizer use, especially near springs and rivers.

- Capture storm water with berms and swales. The goal is to capture the first inch of rainfall and let it filter into the soil.

If you would like more information on Florida Friendly Fertilizing click here

What Makes a Healthy Spring?

That Incredible Water

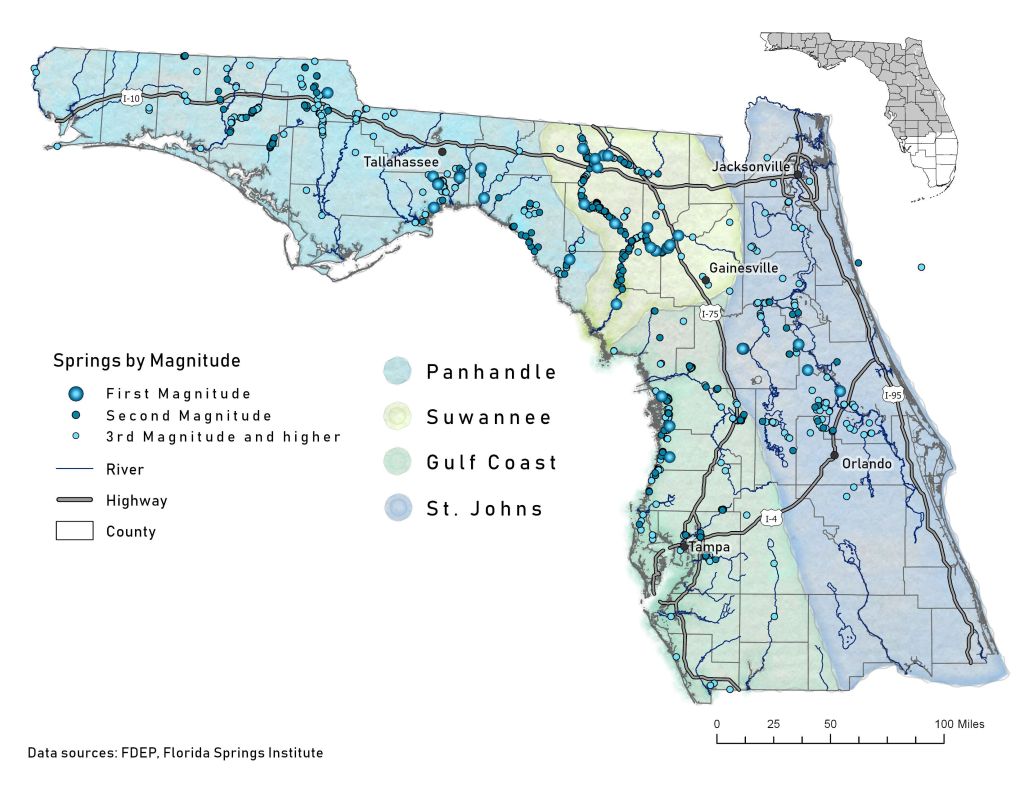

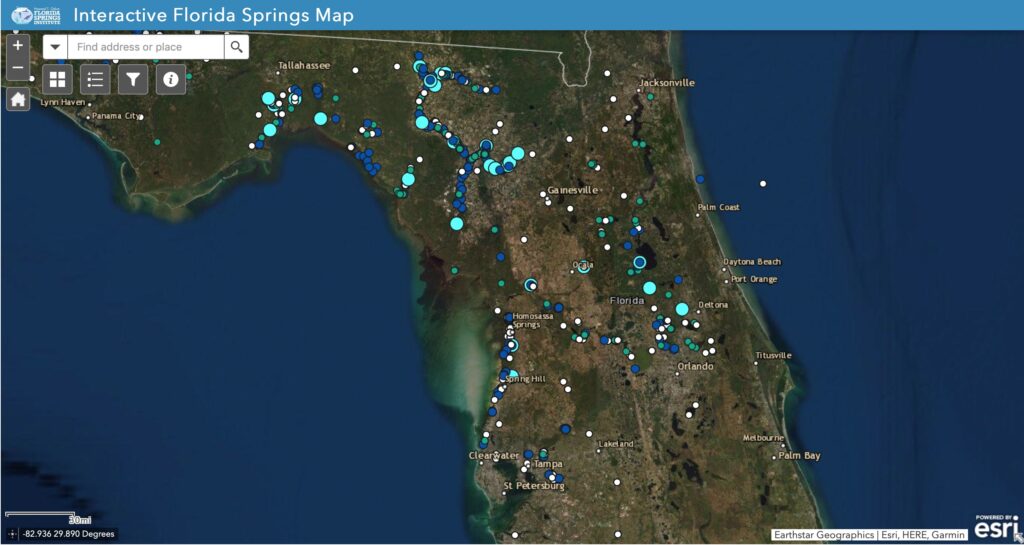

The Florida Spring Region (according to the Howard T. Odom Florida Springs Institute) “comprises more than 27 million acres and extends from south of the I-4 corridor from Sarasota to Okeechobee counties, north through the Florida Panhandle. The Floridan Aquifer supplies water to more than 1,000 artesian springs in Florida, the greatest concentration of large springs in the world.”

The Florida Spring Region (according to the Howard T. Odom Florida Springs Institute) “comprises more than 27 million acres and extends from south of the I-4 corridor from Sarasota to Okeechobee counties, north through the Florida Panhandle. The Floridan Aquifer supplies water to more than 1,000 artesian springs in Florida, the greatest concentration of large springs in the world.”

It may be hard to believe, but we in Florida are sitting right on top of the greatest concentration of springs in the world. The Springs Institute monitors our local springs, as it has for almost a decade. But more than that, it provides educational resources valuable to understand what is happening with our springs. The Springs Institute’s Interactive Map provides a way to understand the number and output of springs across the region. They help you understand what a clear healthy spring is.

A Healthy Spring Checkup

Just like with your annual health checkup, springs have key measurements that let us know they are OK. The primary elements that tell us a spring’s health are:

- Water Volume: the total flow of the spring in gallons or cubic feet/meters.

- Water Clarity: A lack of particles and dissolved organic matter.

- Dissolved material: Everything from dissolved oxygen (indicating health) to dissolved nitrogen and phosphorous (often from fertilizer or septic systems) indicates health.

It is not in the public’s best interest to dry up or pollute any of Florida’s artesian springs. Healthy springs support a vast and abundant assemblage of charismatic and endangered wildlife, nourish our many rivers and lakes during droughts, and are the sought-after playground for tens of millions of visitors each year. Source

Remembering Healthy Springs

Talk to anyone who has lived here a long time. Many will say that for years the mullet were so thick you could catch all you wanted with one throw of the net. With just a few crab traps, you could catch enough to provide an easy meal for your family. The healthy springs we had were crystal clear. You could see a quarter on the bottom and tell if it was heads or tails.

In common terms a healthy spring means clear water. When the water doesn’t have high nitrate levels, small organisms do not cloud the water. But plants are also a big part of a healthy spring. Vegetation provide a place for small worms and crabs to live. It also provides a place for fish to hide and spawn. Once all of these small animals are in a spring, birds and otters will also be there. A healthy spring is alive.

Doing Your Part

You can help bring these springs back to their healthy state by talking with your neighbors. Support our project. Be aware that everything you do around the water can make a difference. Think about fertilizer. Be careful about water use.

And if you can help us please donate. We promise to treat every dollar with care. Your donation will make a difference.

Homosassa Community

The Original Settlers.

Archaeologists estimate that native Americans lived in the Homosassa river area for 10,000 years before the arrival of Europeans to Florida. They chose this area for the bountiful waters teeming with fish, crabs, and shellfish. Today we still crowd to the water for its beauty and the wealth of life we find in the Gulf of Mexico.

Today, a community

Even though we have a rich history, our community today is as tied together by water as ever. We’re a destination for Floridians, with many visitors coming from Hillsborough and Pinellas counties, to the place where Floridians go to “get away”. We have our share of businesses who shelter, entertain, and feed those visitors, and a growing awareness that we’re not going to have this beautiful river if we don’t get busy taking care of it.

What draws this community together?

Ask any guide who takes visitors out to be on our waters, and you’ll learn that they are all conscious of the river’s clarity and the numbers of species they can share with their clients. Our river’s natural beauty is the reason many of them choose to live and work here. It’s also the reason they have a steady stream of guests.

A weak scallop season leaves its mark on our community. Everyone here, whether a guide, a host, or a resident, is connected to the water.

Homosassa is a community that does things together. Festivals that celebrate food and music (Homosassa Arts, Crafts & Seafood Festival and Shrimpa Palooza) draw in artists and musicians. We’re a great place to live, with a pleasant climate and a lower cost of living that makes it affordable to put down roots in paradise.

We are a friendly community. We pull together to put on fantastic festivals with music, food, and arts. We get together and share our river experience.

The river’s decline threatens everyone who comes to Homosassa for its connection to the water. Restoring the river can be a common goal.

Be a river supporter

Our common bond of a community on the water runs through each one of us. Now, unlike ever before, we have a chance to make a lasting change to our river, to give her the love she so richly deserves, and to restore her health.

Don’t let a chance to share this river mission go by. Keep the goal of river restoration in the front of your mind. Talk with your neighbors. Make sure our leaders know how important this restoration is to you and our community.

Please Donate to help us make this enduring change possible. All donations help us complete the restoration sooner. We’re making amazing progress, but we still need your help. Community Strong.

Great Blue Heron

North America’s largest Heron

You may have noticed that we’re pretty fond of the Great Blue Heron. These water fowl are beautiful and majestic, but equally important, they live near the water. Like many of us, these dignified wading birds depend upon this river for their survival.

Highly adaptable, these birds range all across North America, and are as home in southern Alaska as they are her in Florida.

Highly adaptable, these birds range all across North America, and are as home in southern Alaska as they are her in Florida.

Stealthy Hunters

These birds feed by wading into waters, and waiting for prey to swim close. Then with a thrust of their sturdy bills, they capture prey. They also forage on land, hunt from floating objects, and stalk prey in grasslands.

Like the Anhinga and Cormorant they eat mostly fish, but also frogs, salamanders, turtles, snakes, rodents and other birds.

Social Life

These birds breed in colonies, often nesting with other birds. They nest higher up in trees, usually 20 to 60 feet up in the air, but sometimes lower or on the ground on predator free islands. The males choose a nesting site and puts on a display there to attract a mate. Displays include flying above the colony with its neck extended, and stretching its neck out with its bill pointed upward. Hey, this is exciting to lady herons!

These birds breed in colonies, often nesting with other birds. They nest higher up in trees, usually 20 to 60 feet up in the air, but sometimes lower or on the ground on predator free islands. The males choose a nesting site and puts on a display there to attract a mate. Displays include flying above the colony with its neck extended, and stretching its neck out with its bill pointed upward. Hey, this is exciting to lady herons!

And when it comes to nesting, it’s a team effort. The female (mostly) builds the nest, but the male (mostly) gathers the materials. And when mama lays 2-7 light blue eggs, the pair take turns keeping the eggs warm and protected. And both parents feed their young, regurgitating food for about two months while the young chicks mature to independence.

They rely on us

Keeping these beautiful birds close to our shores and in our neighborhoods depends on their being able to feed and nest there. Healthy springs provide the right type of habitat. Habitat restoration has an almost immediate impact on fish species present in the restoration area, with increases in numbers and diversity occurring over just a few years. We can ensure that these and other species have a home close to us by caring for our waters, and returning them to having the rich diversity that they had for years. You can help by keeping their habitat in your thoughts, sharing those thoughts with your friends and acquaintances, and supporting our restoration efforts.

Keeping these beautiful birds close to our shores and in our neighborhoods depends on their being able to feed and nest there. Healthy springs provide the right type of habitat. Habitat restoration has an almost immediate impact on fish species present in the restoration area, with increases in numbers and diversity occurring over just a few years. We can ensure that these and other species have a home close to us by caring for our waters, and returning them to having the rich diversity that they had for years. You can help by keeping their habitat in your thoughts, sharing those thoughts with your friends and acquaintances, and supporting our restoration efforts.

Please share this article and all of our information with your friends and neighbors. Become one of our flock.

Where we get our grass

Where do you get your grass?

When we restore the river, we use eelgrass to establish the base of the ecosystem. Vallisneria Americana or “eelgrass” is also known as tapegrass. And we buy it from companies that grow it in controlled conditions.

It’s critical when planting eelgrass not to take the grasses from one location and move them to another. We grow our grasses in nurseries or “mariculture” (marine agriculture) centers. This way we get grasses that are exactly the species we are looking for. We also can ensure that we’re not introducing other species into the river at the same time. Our grasses are clean and free from organic and biological contaminants. Learn more about our restoration process here.

Tracking our plants

We use grasses that are genetically tagged. Tape grass spreads both by putting out runners or rhizomes, that pop up and create new plants close to the parent, and by seeding. Many times mature plants put out flowers on long straight or corkscrew stems.

Female flowers float on the surface, going up and down with tidal action. Males release pollen, fertilizing the surface female flowers. The flowers release seeds to take root wherever tides and currents take them.

Hungry manatee sometimes pull up whole plants including the root. Being messy eaters, often plants will drift away from feeding manatee. Some plants will find their way to take root somewhere else.

Whether through runners, seeds, or being pulled loose, we can identify the unique genetic tag of all of the plants used to restore the river.

Would you like salt with that?

We select rapid growing species of eelgrass because we want the project to take effect as quickly as possible. The project selected “Rock Star” eelgrass for its ability to spread rapidly. Rapidly spreading grasses grow faster than manatee, turtles, and other creatures will be able to eat it. The faster we establish the grass, the faster it begins using nitrogen and phosphorous in the water, leaving water that is not a great habitat for the blue green cyanobacteria Lyngbya, which has take over our inland waters.

We learned that salt tolerance is another important characteristic of eelgrass. A second species called “Salty Dog” is cultivated for its ability to survive storm surges where inland waters become brackish during hurricanes and storm surges. We choose to grow and deploy Salty Dog along with Rock Star, so that we can get the best of both species.

What you can do

Our ecosystem depends on a sound base. Grasses provide the foundation of the restoration project. In the sands and mud below, worms and invertebrates have a home. Above the surface, the grasses leaves host small organisms that are the foundation of the food chain.

Learn more about grasses and their importance to a thriving ecosystem at these sites:

University of Florida Wetlands Plants (see submerged)

Let us know if you have questions about the grasses used in our restoration project. Send us your questions here.